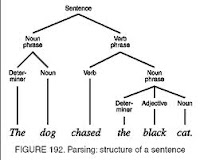

My innate nerdiness is most evident in my love of grammar. Does anyone out there remember parsing, those intricate diagrams of sentence constructions that use to be at the core of grammar lessons? Probably not, but I remember learning how to do it and loving the way I could draw a sentence with its different parts as if it was a subway map. Hours of fun 🙂 And that’s probably why I haven’t disabled the auto-grammar checking thingey on my computer. When one of those dotted green lines appears under a word it brings out the grammarian in me. But there is one construction I am continually getting “told off” about: that vs which. I had to admit that I didn’t really know the difference and although I’m all for breaking rules in writing — especially when writing fiction and dialogue — I do believe you at least have to understand the rule you are deciding to break.

I am taking an enormous leap of faith here, but I am assuming that most of you don’t know the rule of usage for that vs which, and that there are even some out there who find it interesting. So on behalf of all of us, I have done some studying up and here are the results:

The difference seems to lie in the idea of restrictive or limited meaning. If the clause you are writing is about to give information that is key to a specific noun then you use that. Here’s an example:

1. The sentence that I wrote is true. In other words, of the millions of sentences written in the world, the true one is the one I wrote.

2. The sentence, which I wrote, is true. In other words, there are many true sentences which have been written, but the one I am referring to now was written by me.

The use of that in sentence 1 limits the noun to one specific thing within a galaxy of similar things. The use of which in sentence 2 adds interesting information about the one thing I am talking about.

But notice… my beloved little commas separate the clause beginning with which from the rest of the sentence. This is key to the use of the word and a surefire way to know if the usage is correct or not. The word that is part of the same clause as the noun and so does not need to be cordoned off by commas. And as if this wasn’t exciting enough, here’s another rule: the word that is used for inanimate objects and not people. When discussing people, who is correct ie

The boy who stole my heart is now in prison.

The boy that stole my heart is now in prison might be a lyric in a country western song, but it is not to be used in formal prose.

And that brings us to the real heart of the matter. Does it really make a difference? Although I do believe that most grammatical rules do make a difference, this one I am less rigid about. But that is because I am no longer writing theses or technical reports. I’m writing fiction and poetry and much of my writing uses dialogue, and let’s face it, people speak the way they speak, whether it is grammatical or not. So in the final analysis, I will continue to break the rule when it makes sense to do so. But I must admit, it feels better knowing the rule that I am breaking — or should I say, it is better knowing the rule, which I am breaking…..

Why is it whenever I read grammar posts I panic sure I’ve been confused ,completely lost all along? I think it’s something to do with thinking it through. Thanks for putting it so simply.

I think I belong to the Don Marquis ‘Archy and Mehitabel’ school of grammar….

That’s really interesting. I also struggle with ‘that’ and ‘which’ and I do want to get it right, so this is helpful.

I just go for whatever sounds right and then leave it to the proof reader.

Clearly, grammar for most is something to be feared, or at least begrudgingly put up with. But weirdly, I find it gives me comfort. Maybe I’ll keep throwing these things at you all 🙂

Hеllo Тhere. I found уouг wеblog the usе of msn.

This is an extremely nеatly wrіtten аrticlе.

Ι’ll make sure to bookmark it and come back to learn extra of your helpful information. Thanks for the post. I will certainly return.

Also visit my page :: awesome toys