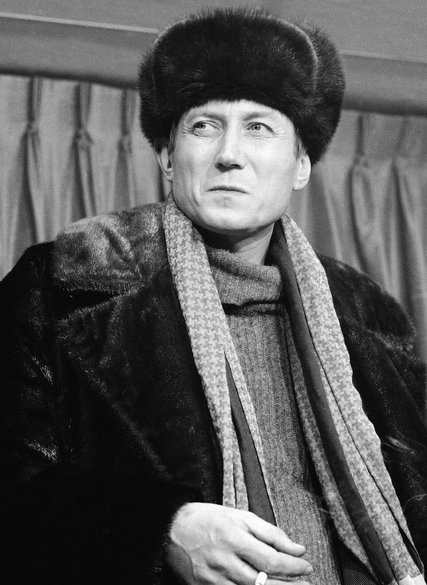

The recent death of Yevgeny Yevtushenko has moved me to write down some thoughts I have been having lately about the intersection of poetry and politics, or actually, any creative writing in general and the present political situation the writer finds her/himself in. It’s not surprising that, as a writer, I have been thinking about this lately. We all find ourselves right now in a very changeable and difficult world. I myself seem to be snared within complex political situations on a global basis — Brexit on one hand, the Trump presidency on the other hand, Cambodia sitting on a shoulder.

The NY Times has written an excellent article about the life and work of Yevgeny Yevtushenko and how it connected with the changing politics of Russia here. Growing up as a Jew in New York during the aftermath of Stalin and the beginning of Kruschev, Yevtuschenko’s work was often discussed. He himself was not a Jew, but he willingly aligned himself with Soviet Jewry when he wrote and published one of his most famous poems, Babi Yar:

There are no monuments over Babi Yar.

But the sheer cliff is like a rough tombstone.

It horrifies me.

Today, I am as old

As the Jewish people.

It seems to me now,

That I, too, am a Jew.

These were brave and dangerous words for him to write, but he believed that speaking out in this way was one of his roles as a poet. This is exactly what I am struggling with now. Is this really one of our roles? Do I dare?

Poetry is an extraordinarily judgmental business. That statement in itself will probably anger some people, but I believe it is true. And I don’t only mean editors making the judgment about whether they want to publish something or not. No matter what sort of poetry you write, there will be some other poets who will speak out against it. The Russian poet Joseph Brodsky once said about Yevtushenko, “He throws stones only in directions that are officially sanctioned and approved.” To some, you are not being ‘political enough’ unless you are threatened with the gulag. So, what is ‘political enough’? If poets can’t agree, or even sometimes civilly agree to disagree about what poetry is, how can we answer such a question?

This past week I led a workshop with a group of Cambodian teachers of English in the theory and practice behind my NGO, Writing Through. We discussed the difference between English poetry and Khmer poetry, the latter being very strict in form and content. One of the teachers eventually asked, “How can you tell if a poem is good or bad?” I smiled and said, “All poems are good. Some may be more beautifully crafted or sophisticated than others, but there is no such thing as a bad poem.” It sounded glib, but I knew I was speaking what is true for me. Some may condemn me for shying away from confrontation or call me a coward for refusing to judge, but to me, a poem, no matter how simple or even awkward, is successful if it connects with even one reader. I don’t believe that art and judgment need to be so closely linked. To me, judging art misses the point.

And that brings me back to the question of poetry and politics. Must poets write about politics? Is poetry essentially a political art form? Is all art political, in one way or another? These are questions I will be investigating further when I run a workshop on the subject with a writers’ group in Singapore at the end of April. I don’t expect answers then and I don’t have them now. But I will say that every time I choose to write something personal rather than political (not that I believe that the two can really be separated), I can hear the voices of some condemning me for cowardice. Every time I write about love or parenthood or loss, and not about war or corruption, I feel judged. That judgement in itself is a political act, isn’t it?

Recent Comments