I am sitting in my office at SOAS for the first time since the start of the second term. Careful readers will remember that in October I started this new position at the University of London’s School for Oriental and African Studies (for you non-Brits who might not have heard of this place before). I wrote about it here. The first term was fascinating in ways I expected and in ways I didn’t. During that term I met with a steady stream of students one-on-one, ranging from first year undergrads to third year doctoral candidates. There was even a professor or two thrown in. I chaired a reading by the Malaysian short story writer, Shivani Sivagurunathan, and I led a guerrilla poetry workshop (i.e. the students didn’t know in advance that they would be writing or even discussing poetry — ha!).

This term the plan is to see more students, lead an expository writing workshop for first years, and give a seminar at the Centre for SE Asian Studies. Am I making myself indispensable? I hope so.

These sorts of residencies are weird ducks. Every writer I know wants one. More and more writers are getting them. It might seem like a bit of a scam to some — i.e. what does it mean? what is it for? — but after one term of having my own, I’m here to report that I do think they are very worthwhile. Non-writers still hold writers in a certain amount of awe, silly as that might seem. Facing the blank page is terrifying for most people, and many then seem to forget that all that we are trying to do, really, is communicate our ideas as well as we can. It may sound silly, but I do believe that the greatest service we can do is to remind people of just that. Writing is a tool. We have ideas. We want to communicate them. Writing is one way to accomplish that. How could that be forgotten by so many? I don’t know, but it seems to be the case. So, demystifying the process has been my first task. The fact that I needed to do this was not surprising, though the level of fear was.

But once I can get them from hyperventilating at the thought, I can then go on to my next task which is the language itself. Now, perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised at this, but I was. Most people really struggle with stringing a sentence together. My experience at SOAS is a bit unusual in that most of the people I work with are not native English speakers. But nonetheless, they are here, orally fluent, and have taken on the goal of writing academic papers in English. The amount of help many have needed with basic grammar has surprised me. And to be honest, this has been true of some of the native English speakers themselves. Please don’t think I am complaining specifically about this particular institution. I know that this is a general problem. There is a lot of blame to go around for this, starting at the secondary school system, progressing to the grading of language admission exams. But the biggest problem, I fear, is that there is a belief that the more complicated the sentence structure, the more sophisticated. People seem to think that if you write sentences with many clauses and lots of indecipherable abstract nouns, then you’ll sound smart. The example I always use comes from my own graduate school days when I came upon a sentence in an “important” published text that referred to a plethora of bogus Roscii. Huh? Actually, the author wanted to talk about the large group of people who had been pretending to be part of the Roscius family, even though they were not. Now really….so my second task is to show that there is elegance in simplicity and that the really knowledgable person is the one who can clearly explain what they mean. I do believe this a very noble cause. We are privileged to have a beautifully expressive language. Let’s not f’ it up, guys.

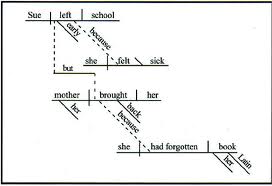

I love being here, surrounded by brilliant ideas and fascinating people. And I love having the opportunity to remind them of the difference between adverbs and adjectives. I’ve now come to believe that if being here helps me find a Cambodian poet to translate, or formulate my ideas on using literature for social change, then so much the better. But if not, it’s still a privilege to be a cheerleader for the language. I’m telling you — I can’t wait to start standing in front of a blackboard and diagramming sentences.

|

| courtesy of grossmont.edu |

I am an avid reader, as you know, but my spelling, grammar and (sometimes) structuring of sentences is pretty poor. At my first school I was taught to spell phonetically and got no grounding in grammar then I moved school and they had already covered it. I’ve never been shown how to properly structure a sentence, still struggle with when to use : or ; and have a whole host of other things that I question when writing. I think that is why I am in awe of people who write…they seem to be able to produce beautiful sentences when I spend most of my time winging it!

C x